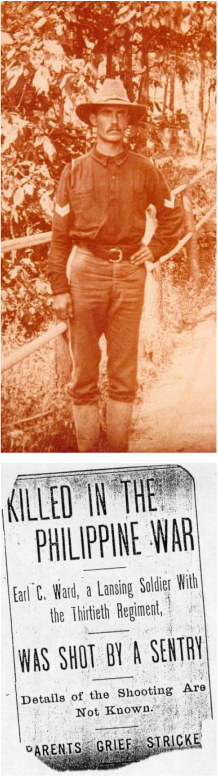

Earl Clinton Ward

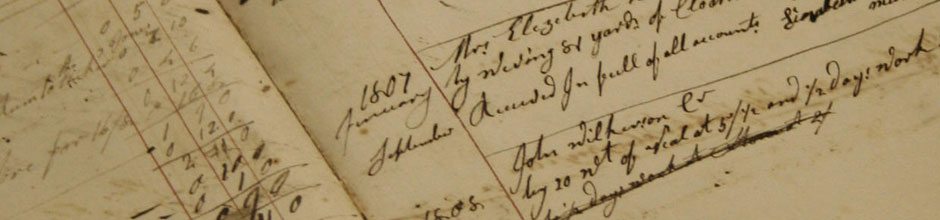

Earl Clinton Ward (1877-1900) was Dr. Hartnell's Great-Great Uncle who fought and was killed in the Philippine-American War. Born in Weedsport, New York on October 16, 1877, Earl and his family moved to Lansing, Michigan when he was four. He graduated from Lansing High School with high honors in 1895 and spent two years at the University of Michigan taking literary courses in hopes of becoming a newspaper writer. After leaving college, he spent one year employed by his uncle at the Wheelbarrow Works before leaving July 13, 1899 for Chicago to enlist in the U.S. Army (with the consent of his parents, of course). Before leaving Chicago for San Francisco, Ward was appointed corporal of the 13th Regiment. From September 23-October 21, his regiment sailed from San Francisco to Manila. He remained in Manila until January 4, 1900, when his regiment left to follow General Theodore Schwan in a march over the mountains toward Tayabas to take part in a "vigorous campaign". Ward wrote home often, describing the country and its inhabitants in entertaining letters that were published in the local papers. On March 4, 1900, Ward was on outpost duty in Tayabas. After posting his relief, he went to sleep in a hammock slung among the coconut trees outside the guard line. Private Charles H. Padfield, who took over as night sentry, soon heard a rustling sound and shouted, "Halt!" A crouching, half-clad figure vanished into the moonlight. A few minutes later, Padfield saw the figure again and yelled "Halt!" (Filipinos had killed many sentries in Tayabas.) Unaware that Ward was asleep in a hammock 20 feet from him, Padfield fired at the suspicious noise. Soon, however, he saw Ward staggering toward him, exclaiming, "What in blazes are you shooting at?" The bullet had entered Ward's shoulder and traveled down his spinal column, resulting in an internal hemorrhage. Ward was rushed to the hospital but died an hour later. As reported, "Ward was one of the brightest and most popular non-commissioned officers of the regiment, and the loss to the company by his decease is a serious one. Touching evidence of his thoughtfulness toward the men under him was shown when, with his dying breath, he exonerated Private Padfield from all blame in the affair." Earl was just 22.