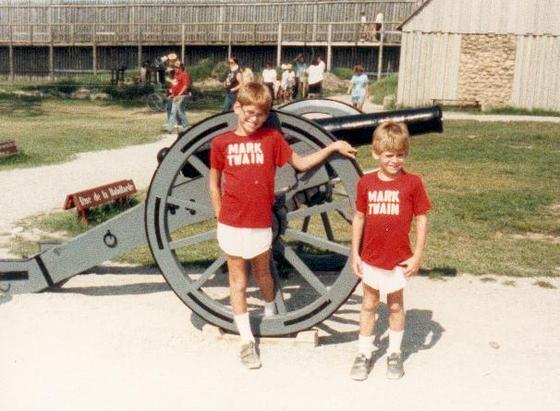

Fort Michilimackinac, Michigan

Fort Michilimackinac... the birthplace of my love for history! Constructed in 1715 by the French as more of a trading post than a military post, Fort St. Philippe de Michilimackinac overlooked the straits that connected Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. These straits were valuable because of the fur trade that was going on between the French and Indians.

I remember walking up to it for the first time and being amazed at its shape and construction. The double-rowed, 18-foot tall cedar walls were carved as pickets and set in a trench (the reconstructed fort only has single-rowed walls). Shaped like a rectangle, it measured 360 feet north-south and 333 east-west. Sentry boxes jutted from each corner and additional guard stations protected the land and water gates.

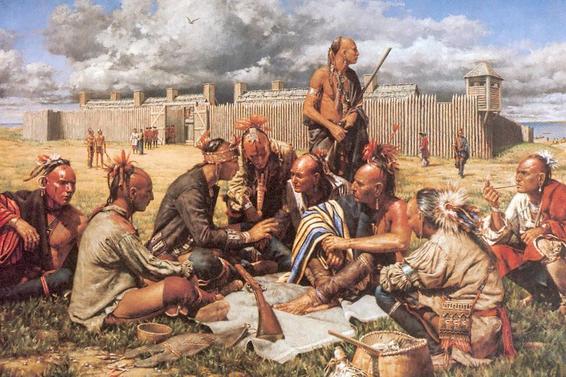

While in an ideal location for spring and summer, it was isolated during the winter months. Since most traders wintered among the Indians, few Frenchmen actually lived at Michilimackinac year round. In fact, only 10 families and a small garrison of 20 French soldiers resided at the fort most of the time.

During the French & Indian War (1754-1763), the British under Captain Henry Balfour arrived to attack the fort... but were greeted instead by the French commander Charles Michel de Langlade who surrendered without a fight (hold the French army jokes). The British allowed the French villagers to continue to live around the fort and seek shelter in it should trouble arise. Balfour departed a few days later, leaving Lieutenant William Leslie in charge of 35 British soldiers and the fort.

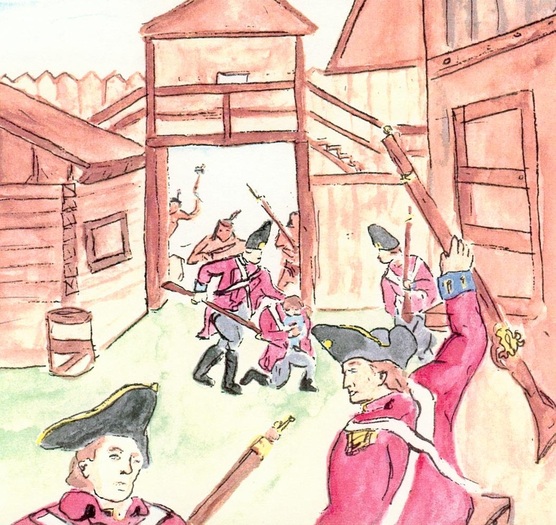

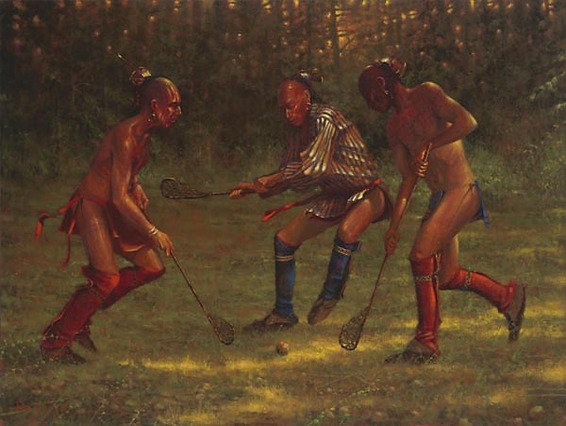

North American territorial battles between the British and French were resolved two months after the Treaty of Paris ended the French & Indian War in British victory. However, the Indians (most of whom had been allies of the French) were excluded from the peace process. The Ottawa Chief Pontiac decided to make a stand and soon planed to capture various forts in the interior, which the British now held. One of his first obstacles… Fort Michilimackinac. (The picture you see above is one I own and have displayed in my office at home.)

Jump to noon on June 4, 1763. The fort's cannon boomed a salute to commemorate the birthday of Britain's new King George III. Former French commander Langlade returned to visit the fort and settlers. As part of the celebration, local Chippewa Indians engaged visiting Sac Indians from Wisconsin in a game of baggitiway. Played much like lacrosse, the Indians raced up and down in front of the fort's land gate, drawing quite a crowd of Indian, British, and French onlookers.

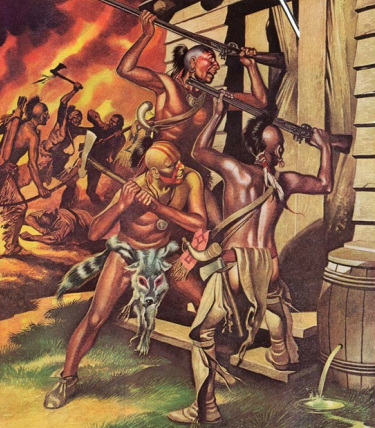

You know that part in a scary movie when the main character decides to go down to the basement to investigate a weird noise... and everyone watching knows this is a bad idea... but there's nothing you can do about it? Okay, cue the British decision to open the main gate of the fort to watch the Indian's play. The Indians' squaws, dressed in heavy and long robes (despite the blistering heat), observed the game while inching closer to the open gate. Suddenly, a Sac Indian launched the ball over the fort wall. Some of the British soldiers casually strolled toward the ball to return it to the field of play. That's when the attack started. The Indians raced through the open land gate, grabbed weapons from beneath their squaws' blankets, and attacked the British troops. Unprepared, the British didn't stand a chance. Within minutes the Indians killed 16 soldiers and captured the other 19, eventually killing five of these prisoners. Around 54 English settlers were also killed. Not a single French settler was harmed. The French commander Langlade did, however, save both Etherington and Leslie from being burned at the stake when he cut the ropes holding them up and challenged the Indians. All three were left unharmed and allowed to go. For a year the Canadians managed the fort until more British arrived under Captain William Howard and retook the fort in 1764.

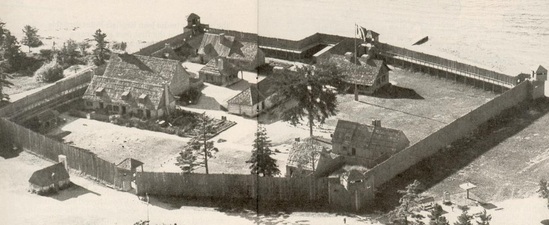

In the winter of 1779-1780 (during the American Revolution), most of the fort was dismantled and transported across the ice of the frozen straits to Mackinac Island where it was used to build a bigger (and better protected) fort. A large cliff and its location hundreds of yards from where ships would be able to fire protected the front of the fort. (It was on level ground, however, in the back.) All of this was in vain because the Second Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolution in 1783 handed the fort to the new American nation.

During the War of 1812, the British captured Fort Mackinac in the first battle of the conflict because the Americans had not yet heard that war had been declared. The victorious British attempted to protect their prize by building Fort George on the high ground behind Fort Mackinac. In 1814, the Americans and British fought a second battle on the north side of the island. The American second-in-command, Major Andrew Hunter Holmes, was killed, and the Americans failed to recapture the island.

Despite this outcome, the Treaty of Ghent forced the British to return the island and surrounding mainland to the U.S. in 1815. The U.S. reoccupied Fort Mackinac, and renamed Fort George as Fort Holmes (after Major Holmes). Fort Mackinac remained under the control of the U.S. Government until 1895 and provided volunteers to defend the Union during the Civil War. The fort even served as a prison for three Confederate sympathizers. (This particular view is from the backside of the fort.)

Following the Civil War, the island became a popular tourist destination for residents of cities on the Great Lakes. Much of the federal land on Mackinac Island was designated as the second national park, Mackinac National Park, in 1875, just three years after Yellowstone was made the first national park.