The following is the Capstone Project completed by Dr. Hartnell in fulfillment of the requirements to earn his M.A.E. through Otterbein University.

Title of Capstone Project:

The Effects of Standards-Based Grading and Differentiated Reassessment on the Metacognition, Motivation, and End of Course Assessments of 9th Grade American History Students

Abstract:

This study attempts to determine whether Mastery Learning (with differentiated reassessment) and Mastery Teaching (within a standards-based curriculum) had a 1) metacognitive and/or motivational effect on how students perceive their learning and 2) whether or not Mastery Teaching had an impact on their mastery of the material when compared to students assessed in more traditional classrooms that did not offer reassessment. Using a standard district American History exam given pre- and post-semester and two student learning and motivation surveys (SMQII and PRO-SDLS), the results showed that being taught in a social studies classroom that utilizes differentiated reassessment and Standards-Based Grading (SBG) does not have a statistically significant metacognitive effect but does have a motivational effect (in particular grade motivation) on non-honors students (U = 1,318, p = .026). Additionally, it was found that students in a SBG classroom produced higher gains on the American History assessment than non-SBG students (t = 1.679, p = .121). Potential interpretations and implications are discussed.

Introduction:

Motivating 14 and 15-year-olds to take an interest in the Magna Carta, the Cold War, and the Election of 2016 – while getting them to learn state content material – is arguably one of the most important things I do on a daily basis. In fact, it was something I set out to accomplish long before I started reading about “why” teachers should. That being said, teaching the same students how to reflect on their educational experiences and developing their ability to identify academic strengths and weaknesses, however, proved to be a bit more challenging. As a result, there was a natural gravitation toward developing metacognitive practices within my classroom when it came to the informational feedback following class assessments. This was a key component of a major grading transformation within my own classroom that resulted in the implementation of Standards-Based Grading (SBG) in 2008. Combining both Mastery Learning and Mastery Teaching practices created differentiated reassessments that now allow me to synthesize student progress and create meaningful units tied to learning targets.

As a teacher who uses a standards-based curriculum to create differentiated reassessments, and as a firm believer in having students reflect on how they did after the initial assessment, I was particularly interested in seeing if these practices truly had metacognitive and motivating effects on how my students perceived their learning. Did this impact their mastery of the material when compared to students assessed in more traditional classrooms that do not offer reassessment or assessment reflection?

As a teacher who uses a standards-based curriculum to create differentiated reassessments, and as a firm believer in having students reflect on how they did after the initial assessment, I was particularly interested in seeing if these practices truly had metacognitive and motivating effects on how my students perceived their learning. Did this impact their mastery of the material when compared to students assessed in more traditional classrooms that do not offer reassessment or assessment reflection?

Literature Review:

The following PDF contains an appraisal of the current literature and examines student-centered approaches to education (including Mastery Learning, Mastery Teaching, differentiation, and Standards-Based Grading) and metacognition and motivation as it pertains to student self-reflection and self-efficacy in social studies classes.

Setting & Sample:

• Suburban high school in Central Ohio with four grades and 1,500 students.

• 327 total students enrolled in 9th Grade American History 1: 124 students in SBG and 203 students in non-SBG (127 Mr. E; 76 Mr. O).

• 232 students participated in the two surveys: 116 surveys from SBG and 116 surveys from non-SBG (80 Mr. E; 36 Mr. O).

• 327 total students enrolled in 9th Grade American History 1: 124 students in SBG and 203 students in non-SBG (127 Mr. E; 76 Mr. O).

• 232 students participated in the two surveys: 116 surveys from SBG and 116 surveys from non-SBG (80 Mr. E; 36 Mr. O).

Data Collection:

Two surveys were administered during Final Exam Week (Dec 16-18, 2015): Glynn’s SMQII and Stockdale’s PRO-SDLS.

Scores from the American History 1 Start of Course Assessment (SOCA) and End of Course Assessment (EOCA) were also used. The SOCA was given Aug. 18-20, 2015; the EOCA was given Dec. 16-18, 2015.

Scores from the American History 1 Start of Course Assessment (SOCA) and End of Course Assessment (EOCA) were also used. The SOCA was given Aug. 18-20, 2015; the EOCA was given Dec. 16-18, 2015.

Research Question #1:

Does being taught in a classroom that utilizes differentiated reassessment within a standards-based curriculum have a metacognitive effect on how 9th graders perceive their learning?

Answer:

NO.

Answer:

NO.

Research Question #2:

Does being taught in a classroom that utilizes differentiated reassessment within a standards-based curriculum have a motivational effect on how 9th graders perceive their learning?

Answer:

YES for Factor 5 among non-Honors (Factor 5: SBG M = 4.384, non-SBG M = 4.096, U = 1,318, p = .026)

NO for all other factors and groups.

Answer:

YES for Factor 5 among non-Honors (Factor 5: SBG M = 4.384, non-SBG M = 4.096, U = 1,318, p = .026)

NO for all other factors and groups.

Research Question #3:

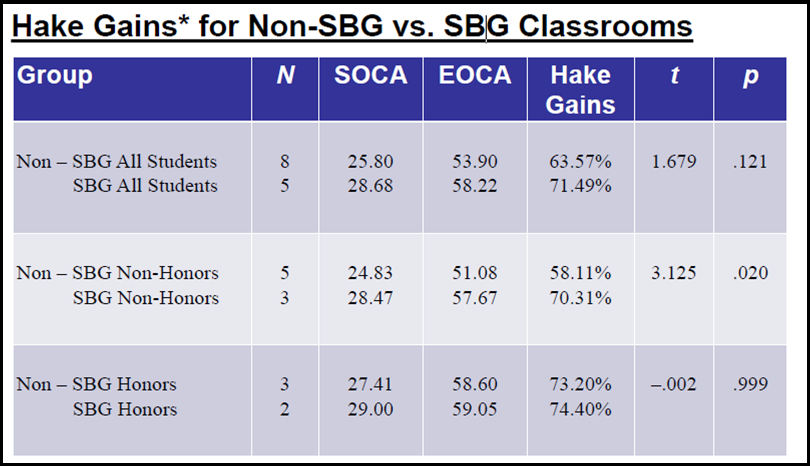

Does Mastery Teaching have an impact on the mastery of the material by 9th graders when compared to students assessed in more traditional classrooms that do not offer reassessment?

Answer:

YES.

Answer:

YES.

Hake Gains:

* A “Hake Gain” is the increase in each student’s pre-test score divided by the average increase that would have resulted if each student had a perfect score on the post-test. It is a meaningful measure of how well an intervention works when comparing populations that have different pre-test scores (Hake, 1988). For example, to calculate the Hake Gain for the non-SBG students ... (EOCA – SOCA) / (70 – SOCA) ... (53.90 – 25.80) / (70 – 25.80) ... 28.1 / 44.2 = 0.6357 ... There was a Hake Gain of 63.57% for the non-SBG students.

Factor 5:

Of all the survey factors that came back statistically significant, it was Factor 5 (Grade motivation) that remains the most curious. The 64 non-honors in my SBG classroom that completed the SMQII scored significantly higher in grade motivation than the other 54 non-honors/non-SBG.

Why?

1. Hope…? Perhaps non-honors students have never been faced with such a detailed breakdown of their performance on a unit test – and in providing them with areas of weaknesses and strengths, non-honors students see that “all is not lost.” There is hope that they can still demonstrate to me that they do, indeed, know the material.

2. Ownership…? Perhaps non-honors students take ownership of their own grades now that they have been handed the keys to reassessment. If they want a better grade, they must do reassessment. By cutting out the ability for them to make excuses as to why they did not master the material the first time through and showing them how to fix their grade, they take ownership of their education.

3. Me against the world…? Perhaps non-honors students no longer see me, their teacher, as the “bad guy” who gave them the “bad grade.” By offering multiple opportunities to be 58 reassessed, I show my non-honors students that I truly am interested in seeing them do well – otherwise I would just give them their “D” and move on. By tearing down the traditional walls that often separate teachers and students, education can be viewed as a partnership rather than “me against the world.”

4. I learn better this way…? Perhaps non-honors students struggle with traditional standardized tests. Unfortunately, until such tests disappear, students still need to know how to take (and be successful on) these tests. However, such practice can be afforded them in my classroom because poor performance does not necessarily mean they do not know the material. In writing an essay, opting for verbal reassessment, or completing a piece of poetry or a song, these students prove they know the material. Their low performance came not in knowing the material – but in not knowing the test. After being exposed to the content numerous times following assessment (often in a manner that played into their specific learning style), something “clicked.” Quite realistically, the mnemonic devices concocted to rhyme portions of the Bill of Rights or the Gettysburg Address for a song written as part of reassessment helps “re-teach” that material in a way that this student can recall when faced with a question on a standardized test about the first 10 Amendments or the significance of President Lincoln’s speech. Students take what they missed the first time around and repackage it in such a way that now they are their own teacher. Reassessment effectively gave them a way to learn and retain content information that can be applied to future material and future assessments.

5. Fear of God…? Perhaps knowing that their parents/guardians, administrators, counselors, and coaches all know that they had two weeks to improve their unit grade… and they chose not to complete any reassessment… puts the onus square on them.

Why?

1. Hope…? Perhaps non-honors students have never been faced with such a detailed breakdown of their performance on a unit test – and in providing them with areas of weaknesses and strengths, non-honors students see that “all is not lost.” There is hope that they can still demonstrate to me that they do, indeed, know the material.

2. Ownership…? Perhaps non-honors students take ownership of their own grades now that they have been handed the keys to reassessment. If they want a better grade, they must do reassessment. By cutting out the ability for them to make excuses as to why they did not master the material the first time through and showing them how to fix their grade, they take ownership of their education.

3. Me against the world…? Perhaps non-honors students no longer see me, their teacher, as the “bad guy” who gave them the “bad grade.” By offering multiple opportunities to be 58 reassessed, I show my non-honors students that I truly am interested in seeing them do well – otherwise I would just give them their “D” and move on. By tearing down the traditional walls that often separate teachers and students, education can be viewed as a partnership rather than “me against the world.”

4. I learn better this way…? Perhaps non-honors students struggle with traditional standardized tests. Unfortunately, until such tests disappear, students still need to know how to take (and be successful on) these tests. However, such practice can be afforded them in my classroom because poor performance does not necessarily mean they do not know the material. In writing an essay, opting for verbal reassessment, or completing a piece of poetry or a song, these students prove they know the material. Their low performance came not in knowing the material – but in not knowing the test. After being exposed to the content numerous times following assessment (often in a manner that played into their specific learning style), something “clicked.” Quite realistically, the mnemonic devices concocted to rhyme portions of the Bill of Rights or the Gettysburg Address for a song written as part of reassessment helps “re-teach” that material in a way that this student can recall when faced with a question on a standardized test about the first 10 Amendments or the significance of President Lincoln’s speech. Students take what they missed the first time around and repackage it in such a way that now they are their own teacher. Reassessment effectively gave them a way to learn and retain content information that can be applied to future material and future assessments.

5. Fear of God…? Perhaps knowing that their parents/guardians, administrators, counselors, and coaches all know that they had two weeks to improve their unit grade… and they chose not to complete any reassessment… puts the onus square on them.

Conclusions:

Being taught in a social studies classroom that utilizes differentiated reassessment within a standards-based curriculum does NOT have a metacognitive effect but DOES have a motivational effect (in particular GRADE motivation) on non-Honors students.

SBG students also produce higher Hake Gains (especially non-Honors) on the EOCA than non-SBG.

SBG students also produce higher Hake Gains (especially non-Honors) on the EOCA than non-SBG.

Selected References:

Glynn, S., Brickman, P., Armstrong, N., & Taasoobshirazi, G. (2011). Science motivation questionnaire II. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(10), 1159-1176.

Stockdale, S., & Brockett, R. (1991). Development of the PRO-SDLS. Adult Education Quarterly, 61(2), 161-180.

Stockdale, S., & Brockett, R. (1991). Development of the PRO-SDLS. Adult Education Quarterly, 61(2), 161-180.

Capstone Paper (in its entirety):

The following are PDFs of Dr. Hartnell's Capstone Project (in its entirety) and Dr. Hartnell's Poster Summary used during his Capstone Defense.