What's a C.A.R. Project?

The Problem with the Traditional Research Paper

|

Ah,

the research paper.

Your parents did them. Your grandparents did them. Even your teachers did them. The research paper has become a "rite of passage" for high school students. But should it? According to Dr. Carol Gordon of Rutgers University, “Research papers are now universally accepted as a benign activity, evidenced by the prevalence of standards and objectives for research skills in school curricula. They have become a staple in the educational diet of the high school student. Research papers have become equivalent to ‘Take two aspirins and call me in the morning.’ It doesn’t seem to do any harm… and may even do some good. Educators adjust the dosage for older or more advanced students: the length of the paper grows with the time allotted to the task but the prescription is the same. Librarians promote the research assignment because they want students to get better at searching, retrieving, and evaluating information. Teachers see it as an opportunity for sustained writing. Parents like it because it is good preparation for college. Everyone likes it because it gets students into the library and reading. That being said, is there something wrong with research as it is traditionally taught in secondary schools?” Dr. Gordon answers her own question by providing three key problems with traditional research papers below. |

PROBLEM #1: Traditional

Research Papers Lack Active Student Involvement

|

With the traditional research paper, students

are asked to choose from a list of topics, all of which are outside classroom

curricula but are typically "high interest" and/or controversial topics. The

assignment requires students to apply critical thinking skills like comparing

and contrasting.

This kind of assignment is faulty in its design. Science classes have traditionally incorporated research methods in their classrooms and lab exercises. History papers funnel students toward primary sources and appropriate methods of analysis (e.g. cause and effect). The research paper is usually viewed as a function of the English class: it presents independent student work as an external exercise for the purpose of learning how to write a paper. It does not aim to expand a student's knowledge in an academic school subject or to teach methods of investigation specific to an academic discipline. The typical assignment does not stress methodology that ensures reliability and validity of results. It does not provide opportunities for the collection of data, be it quantitative or qualitative, that places the student-as-researcher in an environment outside the world of text and into the real world of phenomena. Now, conducting an interview, administering a questionnaire, or keeping a journal based on observation would place students in an active role of collecting data. The typical assignment does not require students to do research. It asks them to report and reflect on the facts and findings of others and to draw conclusions based on reading. When we look at the methods of the experimental scientist working in a laboratory, or the methods of a social scientist using participant observation to gather data about a cultural phenomenon, there are rigorous standards in place to ensure the validity and reliability of results. With the push toward relevance in our teaching and authenticity in our assessments of student knowledge and skill, it makes sense to elevate our expectations of independent student work from the level of reporting to standards of research as it is practiced by real researchers. |

NOTE: Dr. Gordon's Students As Authentic Researchers: A New Prescription for the High School Research Assignment can be found at the American Association of School Librarians at www.ala.org.

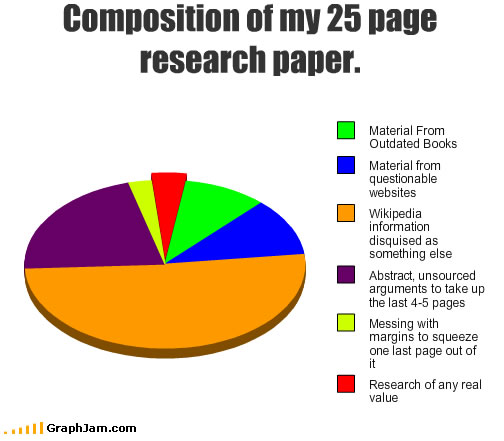

PROBLEM #2: Reports Masquerade as Research

|

The

research project acts as a reporting exercise when student involvement is

limited to information gathering, which is usually demonstrated by reading,

taking notes, and writing a summary. Reporting has masqueraded as researching

for so long that the terms are used interchangeably. In a study that

interviewed students in 9th Grade working through a research assignment,

one student revealed that, "Students'

perception of doing research was writing a grammatically correct report that

was well-presented and provided other peoples' answers to someone else’s

question."

The research process was not internalized in the school library. Rather, it was seen merely as an extension of classroom practice. Students talked about it as though it was a test, which meant creativity and inquiry were not viewed as being part of the process. As such, grades were perceived as the best way to measure success. |

PROBLEM #3: Traditional Research Papers Promote Plagiarism

|

The traditional research paper sends a

clear message to students that they are passive recipients of information.

Teachers are often disappointed with results, especially when confronted with

plagiarism.

It has been suggested that students plagiarize because they are taught to do research under a faulty instructional model that is linear. A step-by-step approach – choosing a topic, narrowing that topic, locating information, taking notes, organizing notes, writing the paper – oversimplifies complex thinking processes that are idiosyncratic and reiterative, driven by the need to know. Even when there is no intent to copy "word for word", many papers are the product of cutting and pasting information: they contain little creativity and virtually no discovery that has been tested, analyzed, and internalized by the learner. These are assignments that can be subverted: students can buy research papers from Internet sites. |

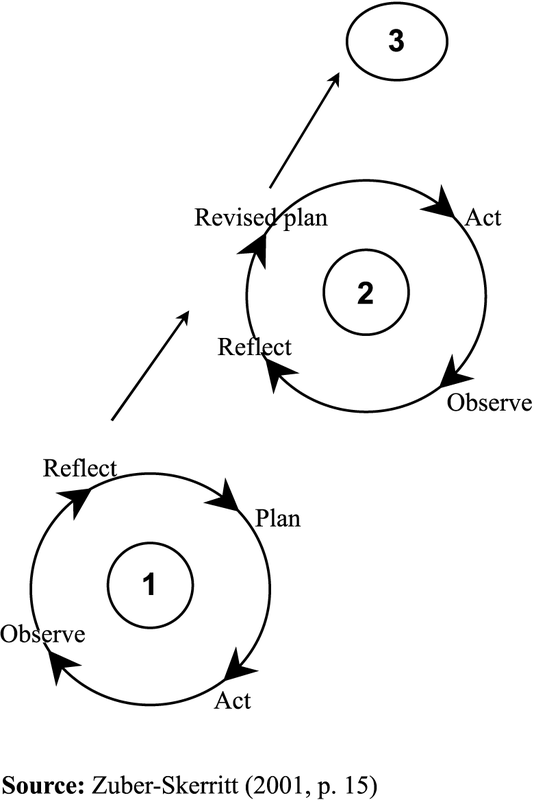

The Solution: Collaborative Action Research!

|

While

"doing a report" is an appropriate fact-finding exercise for short-term

assignments, it has been over-prescribed, eating up time for learning the

investigative methods used by researchers in the real world.

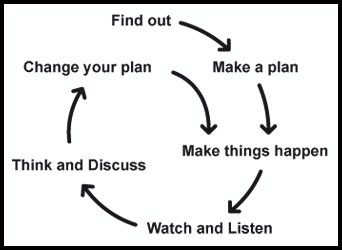

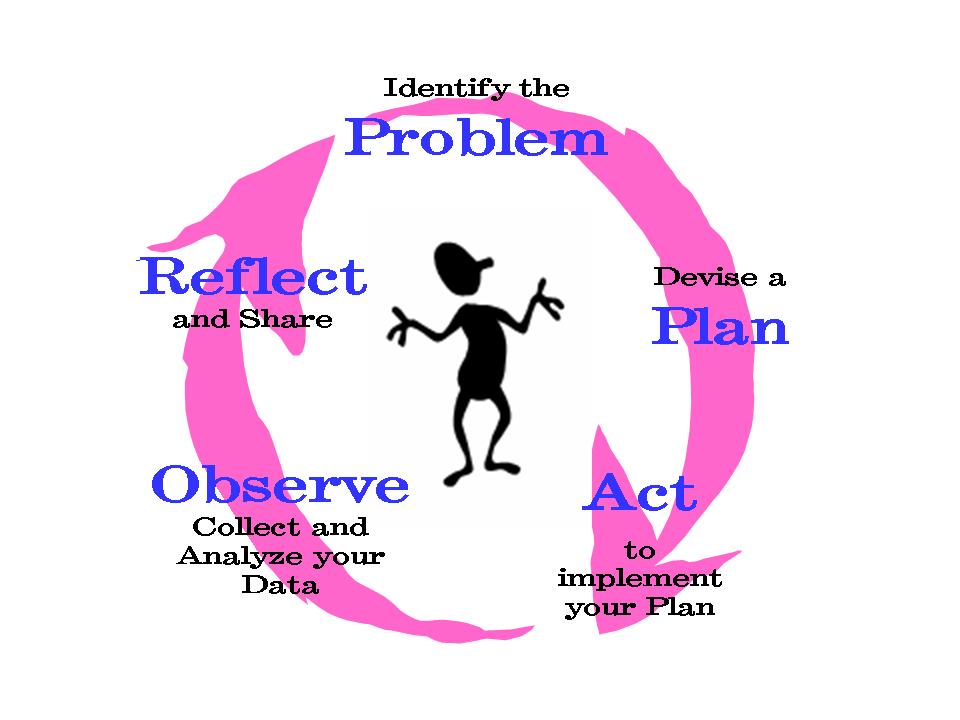

Does "doing research" have to be limited to highlighting photocopied text from books and magazine articles and printing out from Internet sites or CD-ROM databases? Can students successfully use primary research methods to collect their own data? What if teachers and librarians designed research assignments that distinguished between information and data – that is, between facts and ideas recorded in books and electronic sources – and evidence, or data, collected first-hand by the student-researcher? What if teachers and librarians became reflective practitioners who saw the research assignment as an opportunity to gather data, share, and analyze data in order to evaluate and revise the learning task? Enter... the Collaborate Action Research Project! Dr. Margaret Riel of Pepperdine University defines Collaborate Action Research – or simply C.A.R. – as “the systematic and reflective study of one’s actions and the effects of these actions in a school, workplace, or community”. With a C.A.R., researchers examine their work and seek opportunities for improvement. As designers and stakeholders, they work with their peers to propose new courses of action that help improve their surroundings. As researchers, they seek evidence from multiple sources to help them analyze reactions to the action taken. They recognize their own view as subjective, and they seek to develop their understanding of the events from multiple perspectives. The researcher uses data collected to characterize the forces in ways that can be shared with outsiders. This leads to a reflective phase in which the designer formulates new plans for action during the next cycle. C.A.R. is a way of learning from one's practice by working through a series of reflective stages that jumpstart the next phase of research (i.e., perpetual motion). Since these forces are dynamic, C.A.R. is a process of “living one's theory into practice”. Ideally, this kind of research never stops. Your goal is to have another researcher build off of what you started. The diagram to the right shows how Collaborative Action Research is cyclical... and everlasting. |

NOTE: Dr. Riel's A Meta-Analysis of the Outcomes of Action Research can be found at the Center for Collaborative Action Research at www.cadres.pepperdine.edu/ccar/index.html.

How do I conduct Collaborative Action Research?

|

Remember, this form of research is a cyclical process of reflecting on

practice, taking an action, reflecting, and taking further action. Therefore,

the research takes shape while it is

being performed. Greater understanding from each cycle points the way to

improved actions.

C.A.R. is different than other forms of research because there is less concern for universality of findings, and more value is placed on the relevance of the findings to the researcher and its stakeholders. The results of this type of research are practical, relevant, and can inform theory. Critical reflection is at the heart of C.A.R. projects, and when this reflection is based on careful examination of evidence from multiple perspectives, it can provide an effective strategy for improvement. The questions asked by action researchers guide their process. A good question will inspire one to look closely and collect evidence that will help find possible answers. What are good examples of action research questions? What kind of questions will promote the process of deep sustained inquiry? The best question is the one that will inspire the researcher to look deeply at their lives (or their school or their community) and to engage in cycles of continuous learning. Exploring these questions helps the researcher to be progressively more effective in attaining their goals. For Dr. Hartnell's Step-by-Step Guide to creating, writing, and presenting your C.A.R. project, click here. |

|